Physical Products

To understand what follows, it is necessary to grasp the notion of spatial dimension. We live in a three-dimensional world (3D, e.g. m³), where every object has a length, a width, and a height. For example, a box can be described by these three measures. A one-dimensional space (1D, e.g. m or m¹) may be imagined as a straight line, like a ruler. A two-dimensional space (2D, e.g. m²) corresponds to a flat surface, like a sheet of paper. Our brain naturally perceives these three dimensions through vision and movement, enabling us to navigate the world. In scientific or philosophical contexts, however, the notion of dimension can extend to more abstract ideas: a fourth dimension (time), or even theoretical dimensions beyond ordinary perception.

Let us now represent the substance of the Real in its simplest conceivable state, and observe how this state complexifies and which physical products and notions emerge from this complexification.

The simplest conceivable state is one in which the entire substance of the Real (here denoted CELA) exists in a condition of maximum density, without internal differentiation.

I represent this state as a point — not in the geometric sense, but as a configuration in which no discernible spatial extension is yet present.

However, by its very nature as a dynamic substance, CELA cannot remain in this state of maximal density. It must extend.

If it extends along one dimensional axis, it forms a line; along two axes, a surface; along three axes, a volume.

But why stop at three axes? Or at four?

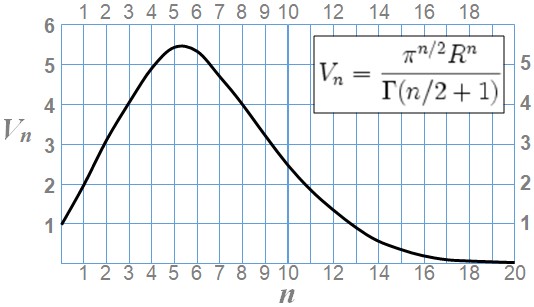

A priori, the substance should be able to deploy along as many dimensional axes as necessary to directly reduce its density — that is, to distribute its being more extensively. Yet the calculation of hypersphere volume variation as a function of dimensionality reveals a maximum located between five and six axes:

Let us see whether this indication of five or six axes will prove useful.

Starting from a state of maximal density, illustrated as a point, let us imagine that CELA extends along a dimensional axis:

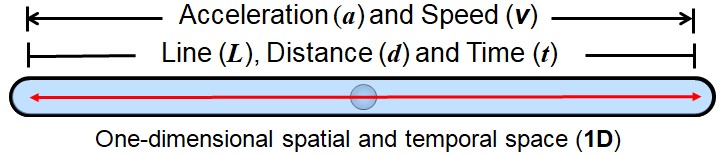

All these physical notions — acceleration, velocity, distance, and time — arise from the exploitation of a single fundamental dimensional axis.

Why include time? Because without time, CELA could not deploy: it would remain in a state of maximal density, without any possible actualization.

This first dimension — simultaneously spatial and temporal — therefore corresponds neither to our Euclidean dimensions (x, y, z) nor to the relativistic model of three spatial dimensions plus one temporal dimension.

Our familiar dimensions of space and time can only be derived products of the fundamental dimensions — effects of the internal dynamics of CELA.

Since CELA exists at every point of the spatial and temporal field it generates, and since this field is finite yet entirely filled by this substance, we may represent each region of space as composed of multiple points of CELA. These points are not isolated, but permanently interrelated.

Now imagine that, in order to reduce its density, this line of points gradually passes from 1D to 5D. This process generates interactions, internal tensions, dynamic exchanges — in short: effects.

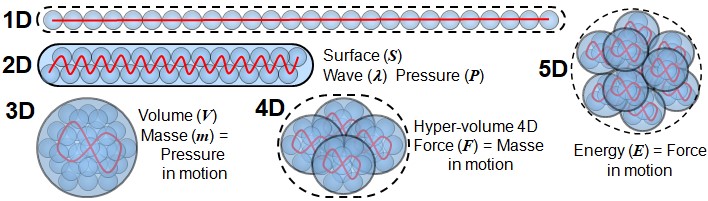

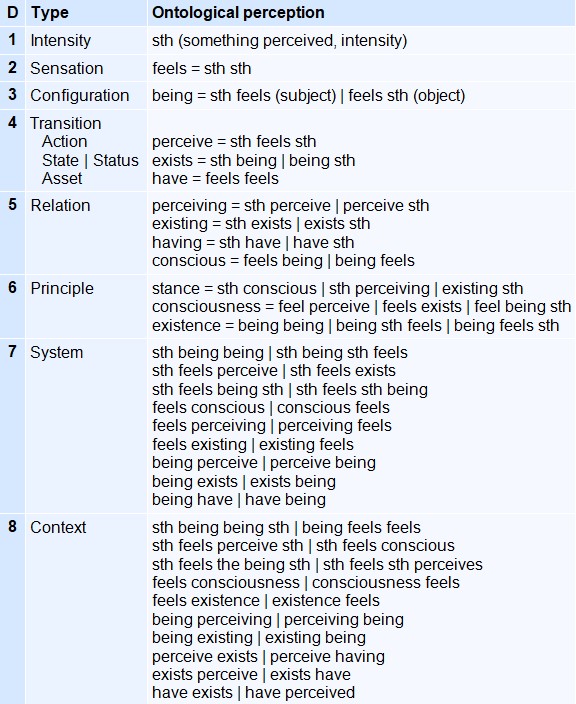

We may represent this complexification as a progressive construction of structures, each level exploiting an increasing number of dimensional axes:

- 1D: a line composed of points. Interaction between points gives rise to distance, velocity, and acceleration.

- 2D: a surface composed of interacting lines, producing waves, pressure, and the first spatial structures.

- 3D: a volume composed of interacting surfaces, where volume and mass emerge (mass understood as pressure in motion).

- 4D: a hyper-volume in which 3D volumes interact dynamically, generating forces.

- 5D: when forces act across distances within a hyper-volume, energy emerges — force in motion.

At each level of interaction between dimensional structures, new physical notions arise naturally. Fundamental physical relations confirm that these quantities align precisely with their axial dimensional levels.

Thus, each physical quantity occupies a specific axial dimensional level.

For example, force belongs to level :

with and , hence:

Likewise, energy belongs to level :

with , therefore:

Why, then, is velocity — defined as a ratio of distance over time () — not of dimension zero?

Because these are axial dimensions, not metric dimensions.

How many axes are required to define distance, time, velocity, or acceleration? Only one.

Thus, all these notions belong to dimension 1, because they all exploit the same generative axis — the axis that simultaneously opens minimal spatial extension and elementary temporal flow.

In extending itself, CELA does not merely generate space. It generates laws, dynamics, and structures.

This point is essential: physical laws are not external to substance. They are the direct effects of its dimensional deployment.

Each new axial dimension exploited by CELA gives rise to new notions — and ultimately to our physical reality.

It is clear, however, that we do not live within these dimensional spaces. More accurately, we are made of them, as is the spacetime we inhabit.

We shall return to this in the sections devoted to physics. For now, rather than attempting to imagine what a substance extended across multiple spatio-temporal dimensions might look like, let us examine its psychic products.

To Go Further

To examine the rigorous foundations of the CdR model:

- image003 — Non-extended state of CELA — theoretical limit

- image004 — Structural optimum 5–6 axes — bound at 8

- image005 — Minimal spatio-temporal axis — distance, duration, motion

- image006 — Emergence of physical forms and notions — multiple spatio-temporal axes

- image007 — Axial correspondence table — physical notions and axial levels

These documents include mathematical formalisms, falsifiability criteria, and academic references.